All over the internet self-proclaimed nutrition experts are instilling the fear of God into people by demonizing one food group or another, or sentencing particular foods to exile without the support of scientific data. A reoccurring topic that certain coaches and ‘experts’ like to preach nonsense about is that of poor old fruit, and how its fructose is going to see your insulin levels launch into orbit along with your body fat. Ok, let’s just take a look at the data and see what’s really going on, and hopefully put the demonizing of fructose to bed where it belongs, but first let’s identify the problem.

A possible reason for the rise in ‘sugar is sugar’ and ‘fructose is the devil’ type posts going around could be because of the rise in popularity of a particular brand of blender. Now I’ve got nothing against blenders, especially the latest trendy one; they’re convenient, you can pack a lot of nutrient dense foods into a relatively small shake and come up with some great tasting recipes and generally, they may help the nation increase the amounts of fruits and vegetables they contain. It’s easy to disguise a few vegetables in a smoothie that somebody might not eat in their normal diet. Some blenders even come with recipe sheets for inspiration and most of the recipes aren’t that bad. The problem that arises however is nutritionally uneducated people (who are also on diets most of the time) are piling up their blenders with as much fruit as possible, most likely under that age old human mechanism of ‘if this is good for me then I need a lot of it.’ It’s not their fault their nutrition knowledge is lacking, if social media and the press are your only sources of nutrition knowledge then you will be behind. So while they’ve made the right choice to increase their fruit intake, let’s not forget fruits are packed with vitamins, minerals and antioxidants, they’ve inadvertently bumped up their calorie intake by several hundred calories. If you blend together one apple, a banana and some strawberries you’re looking at ~180kcals, plus the milk you use to blend it together and the protein powder (can’t forget the gains), you could be getting up into the 250-300kcal range; just from one smoothie. Two smoothies a day and you could be touching 600kcals extra per day. On top of this, I’d bet my last pound (dollar for you Americans) that people don’t account for these extra calories by removing them from other parts of the diet or increasing their energy expenditure to compensate. They just eat normally, train the same and drink two extra smoothies a day, then wonder why they aren’t losing or maybe gaining weight. Just when they’re at their wits end, along comes a big shining knight in white armour who done a weekend course in nutrition or has ‘Dr’ in front of their name, claiming that ‘fruit is bad because it raises insulin so you store it all as fat.’ So it was the fruit all along, not the extra 600kcals you were consuming.

Ok onto the data…

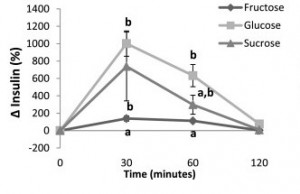

Does fruit really increase your insulin levels as it so often claimed to do? Well, no, it doesn’t actually. A classic study by Horowitz aimed to investigate whether fat oxidation (fat burning) was decreased during exercise due to the reduction in lipolysis (fat breakdown) caused by pre-exercise feeding of carbohydrate. Subject’s received 0.8g/kg (~60g) of glucose or fructose solution, or remained fasted, and one of the measures taken during the study was plasma insulin concentrations. As you can see in the diagram (Fig.1), fructose ingestion hardly elevated plasma insulin levels above that of fasting levels.

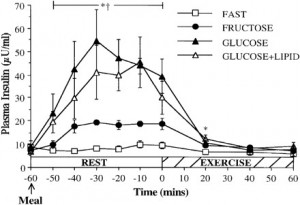

In another study authors found again that glucose and sucrose supplementation significantly increased plasma insulin levels compared to fructose (Fig. 2), only this time subjects received 50g of glucose or fructose solution.

Now both of these studies provided their fructose in solution form i.e. drinks, and the last time I checked, you drink a smoothie. Whole fruit on the other hand, does contain fibre, which further reduces the insulin response (Ullrich). Also, it’s worth noting that the amounts of fructose received in the trials was ~60g and 50g respectively, which is the equivalent to around 10 medium bananas, or 5-6 medium apples, or 20 cups of blueberries, or 240g of strawberries. So I think it’s safe to say that the huge insulin spikes from fruit aren’t really much of an issue.

On a slight tangent, an article I found demonizing fructose even had references to back up its claims. However, the authors certainly need a lesson in picking references. For example, the majority of the studies they cite looked at the effects of fructose feeding to rodents in ridiculously high doses (in some cases over 50% of total calories from fructose) one study claimed fructose resulted in less satiety, but they provided the fructose in a drink i.e. no fibre (even a whey shake doesn’t leave you satiated for very long does it!?); another study claimed that fructose consumption was a risk factor to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, by demonstrating that patients consumed 2-3 times more fructose than controls. However this 2-3 times greater consumption also equated to higher caloric intakes of ~200kcals.

Another excellent (sarcasm) reference from this article showed that consumption of a fructose-sweetened beverage led to greater amounts of visceral fat gain than a sucrose-sweetened beverage in overweight/obese humans- sounds promising. However, these drinks provided 25% of energy requirements, so ~156g of carbohydrate (645kcals) if your diet was 2500kcals (which I doubt seeing as the subject’s average body-fat was 35% and the author’s even stated the subject’s reported food intake was higher than the recommendations), and the subjects were allowed to eat an ad-lib, self-selecting diet during the trial i.e. whatever they wanted to. What’s more, total weight gain was similar between the fructose and glucose trials. So, weight gain was the same and subjects were provided with a super dose, high calorie, specially designed fructose drink that isn’t available to the public – please excuse me if I don’t banish fruit from my diet based on this excellent study.

The reason I included the above was to simply demonstrate that you cannot simply use the first article you come across on Google to demonstrate a point, even if it seems backed up by references.

Take Home Message

So we’ve established that fructose doesn’t cause the huge insulin spikes that are sometimes claimed. Instead, the over-consumption of calories (due to now including a couple of calorie dense smoothies into your daily diet) is more likely to be the cause of any fat gain, or lack of fat loss (Sievenpiper).

By falsely labelling foods as bad and off-limits and stating claims that simply aren’t backed up by scientific evidence, you’re simply adding to the negative relationship that dieters can easily form with foods. Fruit is not the evil that some coaches and fitness gurus claim; the research to support their claims has mostly been found in unrealistic studies that have provided excessively high fructose intakes from artificial drinks or products specifically engineered for the study and that aren’t available to the public; and usually fail to account for the extra calories consumed.

By removing fruit from the diet you could be missing out on some great vitamins, minerals and antioxidants. Fruit is not bad, and should certainly not be as much of a concern as the overconsumption of calories and lack of physical activity. Two or three servings of fruit a day certainly isn’t going to do you any harm, but it’s very easy to accidentally push your daily caloric intake up with smoothies; just make sure you include smoothie ingredients in your daily intake.

Further reading:

http://wholehealthsource.blogspot.co.uk/2012/05/how-bad-is-fructose-david-despain.html

http://www.nutritionandmetabolism.com/content/7/1/82

http://advances.nutrition.org/content/4/2/246.full

Horowitz JF, Mora-Rodriguez R, Byerley LO, Coyle EF. Lipolytic suppression following carbohydrate ingestion limits fat oxidation during exercise. American Journal of Physiology – Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1997; 273no. 4, E768-E775

Jameel F, Phang M, Wood LG, Garg ML. Acute effects of feeding fructose, glucose and sucrose on blood lipid levels and systemic inflammation. Lipids Health Dis. 2014; 13(1): 195.

Ullrich IH, Albrink MJ. The effect of dietary fiber and other factors on insulin response: role in obesity. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 1985 Jul;5(6):137-55.

Sievenpiper JL1, de Souza RJ, Mirrahimi A, Yu ME, Carleton AJ, Beyene J, Chiavaroli L, Di Buono M, Jenkins AL, Leiter LA, Wolever TM, Kendall CW, Jenkins DJ. Effect of fructose on body weight in controlled feeding trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Feb 21;156(4):291-304.

To check out more of Stephen Smith See Here:

www.completephysique.co.uk

Twitter: @completephysiqu

Facebook: www.facebook.com/completephysiquept